ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

In 2013, after signing a contract to deliver packages for Amazon, the U.S. Postal Service began requiring postal carriers to work on Sundays. (Rblfmr via Shutterstock)

The Supreme Court heard oral argument on Tuesday in a case that asking the justices to decide how far employers must go to accommodate the religious practices of their employees. Federal law bars employers from discriminating against workers for practicing their religion unless the employer can show that the worker’s religious practice cannot “reasonably” be accommodated without “undue hardship.” The employee in Tuesday’s case, Gerald Groff, is asking the justices to overturn their 1977 decision in Trans World Airlines v. Hardison, which indicated that an “undue hardship” is anything that would require more than a trivial or minimal cost. But after nearly two hours of oral argument, it wasn’t clear that a majority of the court was prepared to do so. Instead, even some of the court’s conservative justices appeared inclined to strike a compromise, leaving Hardison in place, while at the same time making clear that a trivial burden is not enough to justify failing to accommodate an employee’s religious beliefs.

The dispute now before the court arose when Groff, who is an evangelical Christian, declined to work as a postal carrier on Sundays, because he believes that the day should be devoted to worship and rest. Groff offered to work extra shifts, but the postmaster continued to schedule him on Sundays, while at the same time seeking volunteers to cover for Groff. After Groff failed to report to work when scheduled on Sundays, he was disciplined and eventually resigned.

Groff then went to federal court, where he argued that the U.S. Postal Service’s failure to reasonably accommodate his religion violated Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act, which bars discrimination against employees based on their religion. But the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit disagreed. It ruled that giving Groff an exemption from working on Sunday “caused more than a de minimis cost” for the USPS because it affected the rest of his workplace.

Representing Groff in the Supreme Court, lawyer Aaron Streett told the justices that there is “no reason” why employees should receive less protection for their religious practices than workers covered by other federal civil rights laws, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act. The court should interpret the plain text of Title VII to mean that employers should accommodate their employees’ religious practices unless doing so would require “significant difficulty and expense,” Streett argued.

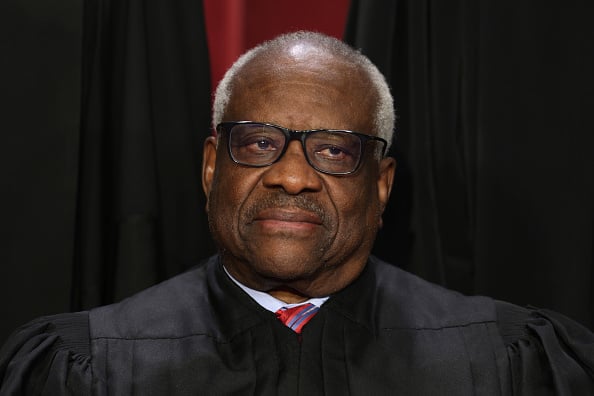

Justice Clarence Thomas, who has previously joined Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch in calling for the court to revisit Hardison, was sympathetic. His questions for Streett focused on whether the Supreme Court in Hardison was interpreting the same version of Title VII that is now before the justices. Groff contends that because it was not, Hardison’s discussion of the “undue hardship” provision is not binding in future cases.

Streett reiterated this point at Tuesday’s oral argument, stressing that the Supreme Court in Hardison was instead interpreting an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission guideline in place at the time.

Two of the court’s liberal justices saw things differently. Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked Streett why the Supreme Court should adopt the “significant difficulty or expense” standard used in other statutes when Congress has declined to do so.

Streett countered that there is nothing to suggest that Congress has accepted Hardison’s “undue hardship” standard. But that comment drew criticism from Justice Elena Kagan, who suggested that no such evidence is required. In cases involving the Supreme Court’s interpretation of statutes, she observed, the presumption of stare decisis – that is, the principle that courts should not overturn their prior precedent unless there is a good reason to do so – “is at its peak” because Congress can always change the law. But in this case, she continued, Congress hasn’t done so, and “you can count on a finger” how many times we have overruled a statutory decision in that context.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson seemed to suggest not only that this was a question better left for Congress, but also that there were good reasons why the court shouldn’t overturn Hardison. Hardison, she observed, “has been on Congress’s radar screen for a very long time, and they’ve never changed it. And I guess I’m concerned that … a person could fail to get what they want in Congress what they want with respect to changing the statutory standard and then just come to the court and say, you give it to us.”

Alito pushed back, suggesting that there may be good reasons for the Supreme Court to revisit Hardison now even if Congress has failed to act. For example, he posited, the Supreme Court may have adopted the “de minimis” test in Hardison because it was concerned that requiring an employer to do more might violate the Constitution; for similar reasons, Congress may have feared that it couldn’t adopt a higher standard in the wake of Hardison.

Kagan was incredulous at this suggestion. “Now,” she said, “we’re guessing as to what the court may have thought in Hardison, which it never said in Hardison, or what Congress might have thought, even though it never said it” – “using our fortune-teller apparatus”?

Representing the Postal Service, U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar told the justices that there is “no reason to dispense with Hardison and discard” the “substantial body of case law that has developed” to analyze undue hardship claims under Title VII. That case law, Prelogar contended, “provides meaningful protection to religious observants.”

Alito, however, appeared unconvinced that the law provides as much protection as Prelogar asserted. He cited “friend of the court” briefs filed by religious minorities, including Sikh, Muslim, and Orthodox Jewish groups. “They all say that is just not true,” Alito told Prelogar, “and that Hardison has violated their right to religious liberty.”

But other conservative justices appeared more amenable to leaving Hardison, if not the “de minimis” standard, in place. Justice Brett Kavanaugh noted that a footnote in Hardison had referred to the employer in that case having done all that it could do without incurring “substantial costs.” That standard, Kavanaugh observed, seems “perfectly appropriate.”

Gorsuch sought to find what he described as “common ground” between Groff and USPS. Because both sides agree that “de minimis can’t be the test … because Congress doesn’t pass civil rights legislation to have de minimis effect,” Gorsuch told Prelogar, why can’t the Supreme Court simply make clear that the “de minimis” test is incorrect “and be done with it and be silent as to the rest of it?”

Prelogar was generally enthusiastic about Gorsuch’s suggestion. “I think, if this court made clear that the ‘de minimis’ language should not be taken literally to mean every dollar above a trifle is immunizing the employers from liability, that is absolutely a correct statement of the law.” And under that test, she continued, the accommodation that Groff sought would still be an undue hardship for USPS, because it had “manifold impacts both on coworkers and on USPS’s ability to deliver the mail.”

More broadly, Prelogar stressed, she wanted to avoid a new standard in which the body of law developed over the past 46 years would be “irrelevant for helping to guide employers in understanding their obligations and courts in applying the statute” in commonly recurring cases involving employees seeking accommodations for their religious practices.

Although Chief Justice John Roberts also seemed open to leaving Hardison in place, he warned Prelogar that the wholesale adoption of earlier cases might not be that simple because, as Alito suggested earlier, the Supreme Court’s religion cases have developed over the years as well. “In other words, if we’re going to do this and say ‘de minimis’ doesn’t really mean de minimis, it means something more significant,” lower courts will “have to take into account our religious jurisprudence as it exists today.”

Prelogar resisted any suggestion that “those developments in the law call into question what the lower courts have done.” Instead, she maintained, courts have looked at the “separate question of, when do the particular burdens and costs on an employer cross that line and are rightly characterized as undue?”

A decision in the case is expected by summer.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.